Kryoflux and DGM: A Preservation Partnership

Written by Dave Beaudoin // March 28, 2016 // In the Museum // No comments

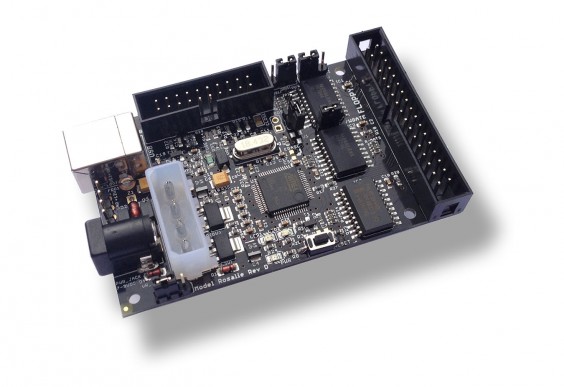

While we usually stress the preservation of artifacts over code, there are times when we receive a rare or unique physical artifact which also contains a digital aspect that should also be preserved. To meet the challenges we face archiving these games in their entirety, the Digital Game Museum has partnered with Kryoflux, a UK based company that specializes in magnetic media. Kryoflux has provided one of their systems to the museum for doing low level archival and forensic reads from digital media. Unlike simply copying code from the disk and transferring it to modern secure digital storage, Kryoflux allows us to take a snapshot of the magnetic charges of a disk’s surface, preserving it precisely as it was when we received it. From this archived copy, we can reproduce the content without risking further damage to the artifact. This code can also be run on an emulator content verification or research.

In the early days of computing, many games were self-published and sold at the local computer store (Richard Garriott got his start this way with one of his first games Akalabeth) or passed around close knit groups of programming and gaming enthusiasts. Our collection features many early indie games as well as beta-test and other non-commercially released versions of games that should be both physically and digitally archived. These games often predate the CD-ROM drive or even the smaller format 3.5″ floppy disk. Additionally we have disks which are formatted for systems like the Amiga, Commodore, or Atari home computers. Using a modern PC or Mac to archive much of this data isn’t really an option. Issues can arise in both data format, physical disk condition, and even early copy protection that relied on manipulation of the disk’s magnetic field.

One of the features of Kryoflux that we’re particularly excited about is the ability to pull low level data off a disk. So even if we don’t have a functioning system that could read a disk, we can make an identical digitization of that disk which could be archived until a system or software-based interpreter comes along that can translate the contents into modern machine or human readable code. This also means that a disk which is partially damaged or rapidly degrading can be stored digitally and any content that can be retrieved from it would still be available, independent of the condition of the artifact. Using Kryoflux we can preserve artifacts in the most consistent and safe way possible while maintaining the ability to partner with researchers and scientists around the world to examine unique digital collateral.

We’d like to thank Kryoflux for supporting the preservation and archival of the important digital artifacts of the game design community and look forward to sharing these digital artifacts with gamers, researchers, and students around the world.